Wednesday, October 20, 2010

Getting back on the horse

As you can see, my initial goal for this project has not been achieved. However, I still plan to finish my backlog, and I have at least 3 or 4 books that I will be adding reviews for in the near future. Stay tuned.

Thursday, January 28, 2010

Prophesying Infotainment

Title: Amusing Ourselves To Death

Title: Amusing Ourselves To DeathAuthor: Neil Postman

Published: 1985

Pages: 163

Reading Time: January 25-January 28, 2010.

Plot Teaser:

From the author of Teaching as a Subversive Activity comes a sustained, withering and thought-provoking attack on television and what it is doing to us. Postman's theme is the decline of the printed word and the ascendancy of the "tube" with its tendency to present everythingmurder, mayhem, politics, weatheras entertainment. The ultimate effect, as Postman sees it, is the shrivelling of public discourse as TV degrades our conception of what constitutes news, political debate, art, even religious thought. Early chapters trace America's one-time love affair with the printed word, from colonial pamphlets to the publication of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. There's a biting analysis of TV commercials as a form of "instant therapy" based on the assumption that human problems are easily solvable. Postman goes further than other critics in demonstrating that television represents a hostile attack on literate culture.

How I Got It:

This was a brand new purchase. While I can't remember the exact store I bought it at, it was likely at a Chapters somewhere in Ontario. Being interested in cultural and media studies in general, I had heard about the praise for this book from many sources, and wanted to check it out. I probably bought this around 2007 or 2008.

The Review:

Neil Postman begins Amusing Ourselves to Death by comparing the worlds of Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, and George Orwell's 1984. While the former warned us about a world where we would choose to be dumb and pleasure-seeking, the latter warned us against totalitarian governments and thought control. In Postman's eyes, we are currently living in Huxley's cautionary tale. Although he was largely writing against the evils of television in 1985, his words still feel relevant today, as we are surrounded with a plethora of digital distractions and contradictory messages. We are so caught up with entertaining ourselves that we do not care about the deterioration of our minds.

In a world that is saturated with pictures and moving images, what are the consequences? What Postman is mostly concerned with here is the movement away from a print-based culture, and a movement towards an image-based one. While he is not against all television programming, as he mentions the harmless nature of sitcoms, he is worried about news production and how people get their information about the world. His attack on the speed of news reports and the focus on sensationalism over content are both applicable to today. Essentially, there is not enough time to process information, and news is simply another form of entertainment. Even if he does sometimes come off as a technophobe, he is always cogent and provides strong appeals for his point of view.

As mentioned, Postman's points are suited to the early 21st century as much as they were to the late 20th. However, it is interesting to consider what Postman would think about today's digitized world. Would he be vehemently against things like social networking, text messaging, and shared encyclopedias, or would he acknowledge that there are some very positive things about our computerized culture? Was he so tied to literary culture, that he did not want to entertain the possible benefits of the modern world? To my mind, the answers to these questions, though fun to think about, do not cheapen the writer's important message. Even if a person thinks that Postman is a man from a bygone era, he or she would be remiss to completely discount his criticisms of our obsession with "the image." Amusing Ourselves to Death is all the more interesting when read from our current vantage point, as we can look back and see that Postman was right about a great many things. We should be all the more on guard and all the more critical of entertainment media for that very reason.

The Verdict:

While it may have been written in 1985, Postman's arguments and his vision of the future are all the more haunting 25 years later. If you are at all interested in cultural studies, or reading about how media works and is designed, this is an excellent primer. It should be required reading not only for first year university students, but for every person who has ever touched a television remote.

4/5

Up Next:

Dragonwings by Laurence Yep.

Overcoming Powerlessness

Title: Radical Gratitude

Title: Radical GratitudeAuthor: Mary Jo Leddy

Published: 2007

Pages: 182

Reading Time: January 21-January 24, 2010.

Plot Teaser:

From one of Canada's most courageous religious writers and social activists comes this invitation to imagine gratitude as the most radical attitude to living life. Gratitude bridges the gulf between our spiritual and material concerns. The dissatisfaction bred into us by advertising and consumerism is soul-destroying and dispiriting. Gratitude arises in that space where our deepest longings find the glass of life to be half-full rather than half-empty. By coming to appreciate the earthy things around us that give true joy, we open the path to greater authenticity and discover what is most real in ourselves. "I believe that at least once in our lives, perhaps once in a year, maybe even once a day, we are recalled to our true selves and to the meaning of our lives. Such revelations are given to each of us in generous recurrence. These invitations can be missed, denied, accepted or rejected - life impresses but it does not impose."

How I Got It:

This was an unplanned addition to my original 40 books. A student lent it to me after we had a discussion about philosophy and personal perceptions of the world. I did not know what the book was about, or what to expect going in.

The Review:

It would be a disservice to call this a self-help book. Mary Jo Leddy strives to provide a different perspective on life, and challenges her readers to approach life with nothing short of absolute joy and gratitude. The title of the book comes from the idea that in a world where humanity is made to feel powerless and to always hunger for more, being thankful for what a person has is a radical act. While she takes on the issue from a religious point of view, her observations about society and consumerism are clear and refreshing.

First and foremost, this is a philosophy book. It is one person's snapshot of affluent societies and what has gone wrong in our dissatisfied civilization. Mary Jo Leddy essentially states that people are driven to feel dissatisfied with their lives, which in turn leads them to desiring more things to fill their lives. It is not a totally novel concept, but her voice is so crystal clear and pleasant that it comes off as a very potent reminder of the problems with a purely consumerist society. Her exploration of power relations between people, themselves, their jobs, and their governments feels timelessly relevant, and makes the book an enjoyable read.

Where the book may put some people off is its solution to all of these problems. While there is a strong call to simply feel grateful for what a person has, and to break free of the cycle of consumption and powerlessness, it comes with a decidedly Christian slant. Who should one feel grateful towards? In Leddy's eyes, the answer is simple: God and Jesus Christ. As a person who is on the fence when it comes to faith and supernatural beliefs, I thought the book did a good job of toeing the line between being absolute faith literature and societal criticism. Usually, the call to God comes at the end of each chapter, and it is fascinating to at least ponder Leddy's answer, whether one is a believer, an atheist, or agnostic.

Even though Radical Gratitude might strike some as being too faith oriented, it is impossible to deny Mary Jo Leddy's sincerity. Her genuine belief in a higher power guiding our lives is not something that is always easy to discuss, but when it is done with such meticulous clarity and respect for non-Christian readers as well, it quickly becomes admirable. And if you are not a person of faith and only want to read about the philosophical sections of each chapter, you can do that as well. The book is equal parts illuminating exploration and soul food.

The Verdict:

Christians and Catholics in particular will no doubt find this book powerful and liberating. With its relevance to modern day problems, and by providing spiritual solutions, it hits that religious sweet spot. The non-spiritual may want to try a chapter or two to see if the book is for them. There is enough intelligent and provoking argumentation for this to be worth a look in either case.

3.5/5

Up Next:

Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman.

Thursday, January 21, 2010

Personal Honesty Amidst Delusions

Title: The Remains of the Day

Author: Kazuo Ishiguro

Published: 1989

Pages: 245

Reading Time: January 17-January 20, 2009.

Plot Teaser:

It is the summer of 1956. Stevens, an ageing butler, has embarked on a rare holiday - a six-day motoring trip through the West Country. But his travels are disturbed by the memories of a lifetime in service to the late Lord Darlington. The Remains of the Day is a nostalgic story of lost causes and a lost love.

How I Got It:

I do not exactly recall where I got this book, but I think it was from a Value Village while on a used book shopping trip with a friend. I am pretty sure that I got it in 2008, though. It was recommended by my friend, and seeing the Winner of the 1989 Man Booker Prize text on the front also helped.

The Review:

"A butler of any quality must be seen to inhabit his role, utterly and fully; he cannot be seen casting it aside one moment simply to don it again the next as though it were nothing more than a pantomime costume. There is one situation and one situation only in which a butler who cares about his dignity may feel free to unburden himself of his role; that is to say, when he is entirely alone."

Such is the worldview of Stevens, an early twentieth century butler who has worked at Darlington Hall for over four decades. By maintaining this strong sense of personal dignity, Stevens believes he may be called a great butler. Consequently, it is his steadfast dedication to his duties and profession that create repercussions in other segments of his personal life. Namely, his relationship with a potential love interest, as well as stifling any sense of self-direction in his rigid life.

Kazuo Ishiguro uses an incredibly fragile and clear style, which match the overall tone of the story - at least at first. As the story begins, Stevens is about to embark on a six day car trip across the country as a reward for working so hard, and to track down an old co-worker, the intriguing Miss Kenton, who is now married. As Stevens travels across Great Britain, he reminisces about his days serving the late Lord Darlington, comparing him to the new house master, an American man named Farraday. Stevens' recollections are often told with such mastery of language, that it would be enough to admire the book for this quality alone. However, as the story progresses we begin to see that Stevens' memory is not as pristine as we are initially led to believe. In thinking back on his service to Lord Darlington, Stevens slowly starts to make realizations about his own life and the people who surrounded him, as well as the state of his deteriorating memory.

The first person narrative style aids feelings of sympathy for Stevens, as well as outright disgust and anger at some of his past decisions and perceptions of situations. While I felt admiration for his high level of professionalism and personal standards of dignity, his complete lack of self awareness and his emotional distancing from events made him quite easy to pity and loathe at the same time. The story is a remarkable example of a narrator showing as much of himself by what he says and does, as well as by what he does not say and do. The style forces the reader to think outside of the situation and not be willingly sucked into Stevens' decorous worldview.

As the story reaches its emotional climax, which is still painted with glorious-yet-saddening restraint, I could not help but feel regret with a very dim glow of hope for Stevens and his life. It is one of the most memorable meetings that I have come across so far in literature, and one of the most perfect endings too. Yes, this is a case of despair and tragedy without genuine purgation, but the end result is all the more powerful because of it.

The Verdict:

Simply put, this is one of the most well-rounded, compelling, and emotionally striking novels I have ever read. Stevens' life story gives us pause and serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of choosing decorum and an over-developed sense of dignity over humanity and honest interactions. I love this book, and I will doubtless be returning to it a couple of more times in the future.

4.5/5

Up Next:

Radical Gratitude by Mary Jo Leddy.

Sunday, January 17, 2010

Delightful Perversity?

Title: Lolita

Title: LolitaAuthor: Vladimir Nabokov

Published: 1958

Pages: 317

Reading Time: January 8-January 16, 2010.

Plot Teaser:

Awe and exhiliration - along with heartbreak and mordant wit - abound in Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov's most famous and controversial novel, which tells the story of the aging Humbert Humbert's obsessive, devouring, and doomed passion for the nymphet Dolores Haze. Lolita is also the story of a hypercivilized European colliding with the cheerful barbarism of postwar America. Most of all, it is a meditation on love - love as outrage and hallucination, madness and transformation.

How I Got It:

This was another leftover in my parents' basement, left behind by my youngest sister when she moved out. I attempted to read it a couple of years ago, but failed because I could not get past the subject matter. I thought I would give it another shot, given its reputation.

The Review:

There is not much new to say about Lolita. Every critical word that could have possibly been spoken about the book has already been mentioned countless times over by other and far more skilled critics than me. So, I will tread on some well-trodden territory, while trying to focus on my own personal experience with the book. If I can remove hyperbole, I will say that the book is certainly memorable for all of its pedophilia and dazzling word play, and it becomes more of an object of curiosity the more one analyzes it.

For the unfamiliar, Lolita tracks the relationship of an aging narrator who calls himself Humbert Humbert, and his perverse obsession with "nymphets," or pre-pubescent girls of a particularly sensual type. The main relationship is between Humbert and Dolores Haze. Lolita. The first part of the book in particular is full of Humbert's own sensual depictions of his violations, and descriptions of the object of his desire. There is certainly perversity involved here, but the way Nabokov presents the topic is nothing short of hypnotic. Humbert is a highly literate European who has come to the trivialistic United States, and his eccentric habits and civilized mind are on full display in Lolita.

I have to admit, I had a very difficult time separating the subject matter from the prose at first. I simply did not "get" the purpose of the book, if a book can have one set purpose. Nabokov's afterword seems to indicate that he hates critical boxes and allegorical interpretations of his works, and that the focus should be more on the process and writing itself. If I were only to judge the book on the beauty, wit, and elegance of its words, it certainly would be one the most perfect books I had ever read. Nabokov's mind and his knowledge of literature and English wit are almost awe-inspiring in the amount of clever and playful thoughts, ideas, and sentences he dishes out here. It is very difficult not to laugh or crack a smile when Humbert dotes upon thoughts of marrying then murdering a woman who is trying to get Lolita involved in more school activities, which would in turn take her away from Humbert's attention. The man is a monster, but one who flits and gambols about in a way that is difficult not to give an "aw, shucks" to.

Humbert is an engaging and evocative narrator. Despite his horriffic failings as a human being, his obsessive personality and gift for elongated description make him hard to ignore. To illustrate this point, here he is talking about Lolita playing tennis:

"My Lolita had a way of raising her bent left knee at the ample and springy start of the service cycle when there would develop and hang in the sun for a second a vital web of balance between toed foot, pristine armpit, burnished arm and far back-flung racket, as she smiled up with gleaming teeth at the small globe suspended so high in the zenith of the powerful and graceful cosmos she had created for the express purpose of falling upon it with a clean resounding crack of her golden whip."

As a lover of books, it is impossible to do anything but admire such in-depth and alluring prose. Simply put, they cast a spell, and the fact that there is also so much tongue-in-cheek in the book makes it a strange combination of satirical comedy and disgusting horror.

In regards to Humbert himself, Nabokov paints him as an unreliable narrator. It is up to the reader to pull his or her mind out of Humbert's and assess what is really happening outside of the flowery narrative style. Humbert constantly refers to his readers as "ladies and gentlemen of the jury," imploring us to sympathize with him and to understand where he is coming from. His goal is to enchant and generate pity. However, by the end of the book only the most gullible or perverse personality would feel anything but disapproval of Humbert and his actions throughout the story.

In the end, I do not want to say "this is a book about one thing or another." Nabokov hates allegorical interpretations, so any allusions to a civilized Europe meeting an immature America are purely speculative. However, as authors are often the worst judges of their own works, I do not believe any extraneous critique of this book can truly be discounted. Yes, it is an incredibly controversial work, but the fact that it has had such an arresting effect on readers and popular culture in general shows the quality of its artistry. Personally, this is a very rich book with plenty to dissect and analyze. Even if one is not prone to critical analysis, he or she can always just enjoy Nabokov's mesmerizing writing style, or cringe through the pedophilia and wonder how a man can actually feel this way for a twelve year old pre-pubescent girl. Or you can even mix the two and delight in Humbert's sick-but-magnetic personality. Afterall, we are all drawn to the strange and twisted, especially when it is wrapped in such pretty packaging.

The Verdict:

There are so many opposing adjectives to describe the content and style of this book. It is this tension between admiration for the form and disgust for the action that is the crux of Lolita. There is a danger in doting too much on one side or the other, but if one can find a balance, he or she should feel nothing short of appreciation for such a complex, trance-like and entertaining work.

4.5/5

Next Up:

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro.

Labels:

20th Century Literature,

Classics,

Lolita,

Vladimir Nabokov

Friday, January 8, 2010

Struggling Against the Light

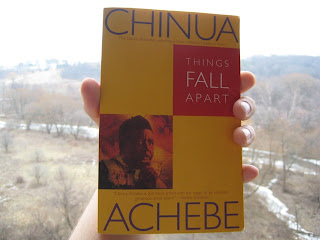

Title: Things Fall Apart

Title: Things Fall ApartAuthor: Chinua Achebe

Published: 1959

Pages: 209

Reading Time: January 4-January 8, 2010.

Plot Teaser:

A simple story of a "strong man" whose life is dominated by fear and anger, Things Fall Apart is written with remarkable economy and subtle irony. Uniquely and richly African, at the same time it reveals Achebe's keen awareness of the human qualities common to men of all times and places.

How I Got It:

A friend suggested I pick this up when she found it at a Value Village, somewhere in Southern Ontario, in 2007 or 2008. I was told it was an excellent book, and recently found out it was one of Time Magazine's Top 100 books from 1923 to 2005.

The Review:

Things Fall Apart tells the tale of an African tribesman in Nigeria named Okonkwo, during an unspecified time in the nineteenth or early twentieth century. The story follows the popular strong man's journey from being a model of work ethic and masculinity, to his downfall in the midst of changing ideas within his own community and the arrival of European colonizers. As someone who is largely ignorant of African literature, this book was a very eye opening experience.

While the book largely follows the successes and failures of Okonkwo, it depicts the day-to-day life and culture of an entire group of people in the process. Umuofia is a community of patriarchal laws and customs, with a focus on manhood and strength. Okonkwo conforms to these ideals, and is often found angry when thinking of past times when "men were men," as he sees the weakening of traditional ideals. As a popular wrestler in his village, he has worked incredibly hard to achieve his three wives and titles, as a way of breaking free from the ghost of his lazy father. Tradition, prestige, and hierarchy are all vital to the nine villages the book depicts, and Okonkwo is the picture of old world ideals fighting against the currents of change.

As a straight narrative, the book tracks the rise and fall of a single man, amidst changing cultural attitudes and outside civilizing intruders. It is the world that Achebe paints with such simple and vibrant strokes that really grabbed my attention in the book. With its unapologetic use of Ibo words and phrases throughout, thankfully made understandable through a tidy two page glossary, one of Things Fall Apart's greatest strengths is its ability to transport the reader to this stark-yet-rich time and place, illuminating the supernatural beliefs and practices of people who simply wish to continue existing. There are shocking rituals involving the killing of young children that are simply taken as an appropriate course of action in certain circumstances, and it is these instances that show the disconnect between the perceived civilized and savage opposites.

While the first part of the book does an excellent job of hilighting the culture of Nigeria's people, the second half deals with colonization and the influence of missionaries on this same culture. The classic irony is presented: Christianity is meant to unify people, but it tears sons from fathers and causes massive turmoil and a line of bodies in its wake. As a work of colonization literature, Things Fall Apart is masterful in the way it takes apart the relationship of colonizer and colonized from the frontlines. The elegance of the book is that it does not preach of the virtues of the savage, as it distinctly shows the good and bad of the people, nor does it preach about the evils of Christian influence. It simply gives an account of events and provides an epitaph for the colonized; a depiction of what many tribes went through.

It would be easy to say that the reason for the book's high praises over the past half-century has stemmed from white guilt. Yes, there should certainly be a feeling of contrition for the symbolic actions depicted here, but as a work of fiction, the book succeeds on its own merits. It offers wisdom that should be taken to heart in dealings with all people, and for that reason alone it deserves whatever praises have been lauded upon it.

The Verdict:

An elegant portrayal of the colonizer and the colonized, Things Fall Apart is a book that gets better the more you think about it. While it may feel slightly alien at first, patience and rumination reward the thoughtful reader. We all want to be left to live our lives in peace, thinking we are doing what is just and right in our own eyes and the eyes of those watching us.

4.5/5

Up Next:

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov.

Published: 1959

Pages: 209

Reading Time: January 4-January 8, 2010.

Plot Teaser:

A simple story of a "strong man" whose life is dominated by fear and anger, Things Fall Apart is written with remarkable economy and subtle irony. Uniquely and richly African, at the same time it reveals Achebe's keen awareness of the human qualities common to men of all times and places.

How I Got It:

A friend suggested I pick this up when she found it at a Value Village, somewhere in Southern Ontario, in 2007 or 2008. I was told it was an excellent book, and recently found out it was one of Time Magazine's Top 100 books from 1923 to 2005.

The Review:

Things Fall Apart tells the tale of an African tribesman in Nigeria named Okonkwo, during an unspecified time in the nineteenth or early twentieth century. The story follows the popular strong man's journey from being a model of work ethic and masculinity, to his downfall in the midst of changing ideas within his own community and the arrival of European colonizers. As someone who is largely ignorant of African literature, this book was a very eye opening experience.

While the book largely follows the successes and failures of Okonkwo, it depicts the day-to-day life and culture of an entire group of people in the process. Umuofia is a community of patriarchal laws and customs, with a focus on manhood and strength. Okonkwo conforms to these ideals, and is often found angry when thinking of past times when "men were men," as he sees the weakening of traditional ideals. As a popular wrestler in his village, he has worked incredibly hard to achieve his three wives and titles, as a way of breaking free from the ghost of his lazy father. Tradition, prestige, and hierarchy are all vital to the nine villages the book depicts, and Okonkwo is the picture of old world ideals fighting against the currents of change.

As a straight narrative, the book tracks the rise and fall of a single man, amidst changing cultural attitudes and outside civilizing intruders. It is the world that Achebe paints with such simple and vibrant strokes that really grabbed my attention in the book. With its unapologetic use of Ibo words and phrases throughout, thankfully made understandable through a tidy two page glossary, one of Things Fall Apart's greatest strengths is its ability to transport the reader to this stark-yet-rich time and place, illuminating the supernatural beliefs and practices of people who simply wish to continue existing. There are shocking rituals involving the killing of young children that are simply taken as an appropriate course of action in certain circumstances, and it is these instances that show the disconnect between the perceived civilized and savage opposites.

While the first part of the book does an excellent job of hilighting the culture of Nigeria's people, the second half deals with colonization and the influence of missionaries on this same culture. The classic irony is presented: Christianity is meant to unify people, but it tears sons from fathers and causes massive turmoil and a line of bodies in its wake. As a work of colonization literature, Things Fall Apart is masterful in the way it takes apart the relationship of colonizer and colonized from the frontlines. The elegance of the book is that it does not preach of the virtues of the savage, as it distinctly shows the good and bad of the people, nor does it preach about the evils of Christian influence. It simply gives an account of events and provides an epitaph for the colonized; a depiction of what many tribes went through.

It would be easy to say that the reason for the book's high praises over the past half-century has stemmed from white guilt. Yes, there should certainly be a feeling of contrition for the symbolic actions depicted here, but as a work of fiction, the book succeeds on its own merits. It offers wisdom that should be taken to heart in dealings with all people, and for that reason alone it deserves whatever praises have been lauded upon it.

The Verdict:

An elegant portrayal of the colonizer and the colonized, Things Fall Apart is a book that gets better the more you think about it. While it may feel slightly alien at first, patience and rumination reward the thoughtful reader. We all want to be left to live our lives in peace, thinking we are doing what is just and right in our own eyes and the eyes of those watching us.

4.5/5

Up Next:

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov.

Juvenile Silliness

Title: Sunlight and Shadow

Title: Sunlight and ShadowAuthor: Cameron Dokey

Published: 2004

Pages: 184

Reading Time: January 3-January 4, 2010.

Plot Teaser:

Thus begins a tale of Mina, a girl-child born on the longest night of the darkest month of the year. When her father looked at her, all he saw was what he feared: By birth, by nature, she belonged to the Dark. So when Mina turned sixteen, her father took her away from shadow and brought her into sunlight. In retaliation, her mother lured a handsome prince into a deadly agreement: If he frees Mina, he can claim her as his bride. Now Mina and her prince must endure deadly trials - of love and fate and family - before they can truly live happily ever after...

How I Got It:

This was another book that I found in a four or five for a dollar pile at Barone's Books, in Stoney Creek, Ontario. I think it was some time in 2008, but I could be wrong. It is a re-imagining of Mozart's The Magic Flute, which I knew nothing about before reading this.

The Review:

Based on a Mozart opera called The Magic Flute, Cameron Dokey's re-imagining is effective young adult fiction with a touch of charm and whimsy. While the book is overly dramatic at times, which I suppose is the point, it is nonetheless entertaining largely as a result of Dokey's structural choices. If you enjoy light-hearted fantasy stories or fairy tales about princes and princesses, this book is a decent bet.

The basic premise is this: Mina is a child of both light and darkness, with her parents being the overseers of the day and the night. On her sixteenth birthday, some incredibly significant event is supposed to occur. Her father abducts his own daughter with the intention of marrying her to a man of his choosing; a long-time apprentice of his. Outside of this plot, the story jumps around to a few other kingdoms where events take place that eventually lead all of the main players to the same place. Oh, and all of them are guided by love and the desire to know their hearts and find their true loves. There are also some magic bells and a flute.

I do not want to spoil everything, but to be honest the story is a bit silly. There seems to be a lack of genuine motivation on the part of Mina's father, and one of his choices late in the book is simply not consistent with the motivations that are clearly visible up to that point. I will simply say he puts his own daughter in a dire situation with her new-found love, when his goal all along was to preserve Mina. To put her in a situation where she could literally die seems unreasonable and just plain stupid. Of course, everything plays out happily in the end, with the power of love trumping all other emotions or logic. People literally fall in love at first sight more than a few times in this book, which make it seem a little hokey. However, I cannot really blame the author for that since she had pre-existing material guiding her.

The most interesting thing about this book is its structure. Every chapter is told through the eyes of a different narrator, which is great if you read the book in large chunks at a time. You get to see the perspectives of the perceived villains as well as the heroes. This gives the book a neat balance and makes sure there is never really a dull moment. The only disappointing thing is that none of the characters really has a distinct voice in the novel, and the writing style generally remains the same for all of them, which is one of syruppy drama. For example:

"I felt a pain so sharp I feared my very bones would splinter and pierce my flesh. This was my father. All my life I had wanted him to know and to love me. The father whom, for all my life, I had wished to know and to love. If he had waited just a few more hours, who is to say what might have been possible between us? But he had not, and so I knew there could be nothing."

Everything is reactionary and laid bare to the point where reason simply does not exist. The only thing that differentiates the narrators is their motivations and locations in time and space. Still, it was nice of the author to attempt to jazz up the adventure in some way.

While I admit the story is charming and whimsical in the way it has no real basis in reality, it is these same traits that slightly distance the reader from the events. Yes, there is certainly humanity, and the first person approach of each chapter ensures a sense of engagement, but any serious reader will likely find themselves not caring much for what happens to these characters because they are in a world where anything is possible. There is never a sense that anything is going to go wrong, and the only real thing to look forward to is discovering who ends up with who. Again, this was originally an opera, so perhaps the point is not in the end results, but in the journey, which is itself an enjoyable one.

The Verdict:

If you have a young daughter and want to get her interested in reading, this might be a good choice. Everyone else will likely approach it with a half-smile for all its fuzzy charm amidst some very safe drama. Fans of The Magic Flute may wish to give this a go, as it does feature some changes in characters' depictions, while offering up a fresh way to re-tell the original tale.

3.5/5

Up Next:

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe.

Sunday, January 3, 2010

Back to the Beginning

Title: Fallen

Title: FallenAuthor: David Maine

Published: 2005

Pages: 244

Reading Time: December 30, 2009-January 3, 2010.

Plot Teaser:

Once expelled from the Garden, Eve and Adam have to find their way past recriminations and bitterness to construct a new life together in a harsh land. But the challenges are many for the world's first family. Among their children are Abel and Cain, and soon the adults must discover how to be parents to one son who is everything they could hope for and another who is sullen, difficult, and rife with insecurities and jealousies. In the background, always, is the incomprehensibility of God's motives as He watches over their faltering attempts to build a life. In Fallen, David Maine has drawn a convincing, wryly observant, and enthralling portrait of a family-one driven (and riven) by passions, jealousies, irrationality, and love. The result is an intimate, in-depth story of brothers, a husband, and a wife-people whose struggles are both completely familiar and yet utterly original.

How I Got It:

I found this hardcover edition sitting in the clearance pile of a Coles Bookstore inside Jackson Square, in Hamilton, Ontario. I believe it was either $4.99 or $5.99. Its premise grabbed my attention, as I have generally been interested in religious and Biblical tales.

The Review:

In Fallen, David Maine uses his imagination to expand upon the Biblical stories of Adam and Eve, and their first sons, Cain and Abel. And he does it backwards. The result is an alluring take on the world's first family; one that offers plenty of real world situations and gives flesh and bone to these familiar mythical figures. Maine creates a story that largely deals with survival, faith, mortal passions, and the quintessential questions of human origins and the role of the supernatural.

Fallen begins at the end of Cain's life. As an embittered old man, he lies alone in a cave, simply waiting to die. From this point of origin, David Maine works backwards, illuminating how things got to their present state. The book is divided into four separate parts titled The Murder, The Brother, The Family, and The Fall. Each section is itself split into ten parts, with chapter titles being repeated throughout, but always having different meanings depending on the part of the story currently being focused on. The book starts from chapter forty, and works its way down to one. This structure lends the book a commendable symmetry, as Maine deserves praise for taking the time to craft the book in such a careful and effective way.

To begin, the original stories that Maine is working from only cover a couple of pages of the entire Bible. With this type of source material, Maine's challenge was to stretch out a very well-known and brief story into a fully realized novel. I believe he has succeeded by providing a book that feels familiar, while being altogether underivative. He infuses each of the four main players with distinct personalities and characters. He manages to make Cain more than slightly sympathetic, while painting Abel as a bit of a simpleton. With Adam and Eve, he paints a less than ideal portrait of a union that is fraught with as much vitriol and animalistic urges, as it is with faith and love. These are real people with their own beliefs, motivations, and questions.

It is the questions that really give the book an extra edge, as they all stem from God's design. Cain is the rationalist who is obsessed with his parents' origins, and wonders why God would put any evil and temptation in Paradise to begin with. He asks free thinking questions about why his parents bother to continue to pay tribute to an allegedly fair God, when His actions have been nothing short of petty and irrational. Oddly enough, Adam and Eve are not altogether unaware of their specious devotion either. This kind of humanity and open questioning of God's motives propels the narrative, and is generally the reason why everything happens. Adam simply does as he is told, because that is all he has ever known, though he has frequent outbursts. Abel is content with his naivete. It is Eve and Cain who provide balance to this line of thinking by asking questions and suggesting alternate ways of living.

At its heart, the book is very literal and human. It is even brutal, in the way it describes the killing of animals, childbirth, Adam and Eve's lust for one another, and even Cain catching his parents in the act. That final scene in particular is startling in its perversity and honesty, and it is emblematic of Maine's tooth and claw approach to the story. While he stays faithful to the main events of the Bible, his expansions are often striking and entirely believable.

The only problems I had with the book were largely synthetic. There are quite a few idioms that get thrown around, and some of the word choice seems out of place for this time period. I also wondered whether mentions of winter and snow were appropriate, especially if the Garden was indeed around the Mesopotamian and North African regions. I realize this is a fictitious time and place, but the historian side of me felt a little odd during these sections. All in all, though, these are minor quibbles against what is otherwise a very captivating interpretation of one of the West's most well-trodden stories.

The Verdict:

Fallen is a book that is enjoyable for the religious and non-religious alike. Its story is so ingrained in Western culture, that non-Jews and non-Christians will be able to enjoy it on its own merits. The faithful would also do well to look into this book, as it makes many poignant challenges towards God in an honest and respectful way. Its questions about God, and its depiction of Adam, Eve, Cain, and Abel as a truly messed up family that is trying to find out its purpose is something anyone can appreciate. It is a story of survival in the wilderness, and all that entails.

4/5

Next Up:

Sunlight and Shadow by Cameron Dokey.

Labels:

Adam and Eve,

Bible,

Bible Stories,

Cain and Abel,

David Maine,

Fallen,

Genesis,

Old Testament

The Pains of Youth

Title: Peter Pan

Title: Peter PanAuthor: J.M. Barrie

Illustrator: F.D. Bedford

Published: 1911 (Wordsworth Edition, 1993)

Pages: 176

Reading Time: December 23-December 30, 2009.

Plot Teaser:

The magical Peter Pan comes to the night nursery of the Darling children, Wendy, John and Michael. He teaches them to fly, then takes them through the sky to Never-Never Land, where they find Red Indians, wolves, Mermaids, and...Pirates. The leader of the pirates is the sinister Captain Hook. His hand was bitten off by a crocodile, who, as Captain Hook explains "liked me arm so much that he has followed me ever since, licking his lips for the rest of me." After lots of adventures, the story reaches its exciting climax as Peter, Wendy and the children do battle with Captain Hook and his band.

How I Got It:

I found this edition on top of a $4.99 bargain table at Chapters in Ancaster, Ontario. I remember also picking up The Wizard of Oz that day, which I really enjoyed. I think I wanted to read a couple of the classic children's stories, since I had never done so before.

The Review:

Most North Americans and Europeans are likely familiar with the story of the boy who would not grow up. Whether it is through this book, or the popular children's film, the story is simple and universal. Essentially, Peter Pan is about the desire to remain a child forever, and to stay in the emotions and ignorance of youth. It follows the life of the Darling children, particularly Wendy, as they are swept off to a magical land of fantasy and adventure, where they slowly forget their past lives and parents. The children desire to remain in Neverland forever, and never want to grow old. It is something most of us can relate to, and the book captures the energy and innocence of childhood.

First of all, the way Barrie tells the story like a paternal figure sitting by the reader's bedside is appropriate for the subject matter. He constantly gives hints of future events, or plays with the narrative by writing about the various avenues the story could take, or what he can talk about, and this creates a sense of distance, while showing off his storytelling ability. He makes the reader an active part of the adventure. If anything, he knows his audience and how to speak to them.

The adventure housed within the pages also moves at a linear and brisk pace. Barrie goes from place to place,

and keeps the reader interested, largely as a result of his storytelling style. It must be said that this book truly is more for children than adults with its handholding style, aside from an allusion to a fairie orgy and Tinkerbell's sexual frustration, that are not enough to take the book out of the realm of children's fiction. Barrie's handling of Peter Pan as a short-sighted and immature boy is also interesting, as I was sometimes not sure whether to like him or loathe him for his arrogance and thoughtless ignorance. Consequently, the themes explored are more than relevant to all age groups, and the ending in particular resonated with me as an adult.

and keeps the reader interested, largely as a result of his storytelling style. It must be said that this book truly is more for children than adults with its handholding style, aside from an allusion to a fairie orgy and Tinkerbell's sexual frustration, that are not enough to take the book out of the realm of children's fiction. Barrie's handling of Peter Pan as a short-sighted and immature boy is also interesting, as I was sometimes not sure whether to like him or loathe him for his arrogance and thoughtless ignorance. Consequently, the themes explored are more than relevant to all age groups, and the ending in particular resonated with me as an adult.Still, the reasons I like the book and why I think many young adults would enjoy it, are also the reasons I do not love it. Maybe I am not looking into the book deeply enough, but it is a pretty basic tale of the growing pains associated with coming of age, and realizing that you are no longer a child. As Barrie says, "two is the beginning of the end." I admire his ability to encapsulate the vibrant energy

of childhood, but feel there is a lack of complexity in the analysis, aside from the ending and his handling of Peter. It may sound like I am complaining about a children's book being a children's book, and I do feel the ending is excellent and the exploration of mothers interesting, but I can not help but feel slightly underwhelmed by the events. It may because I knew the story going in, and felt more like I was playing out something that was already familiar and not needing further discussion.

of childhood, but feel there is a lack of complexity in the analysis, aside from the ending and his handling of Peter. It may sound like I am complaining about a children's book being a children's book, and I do feel the ending is excellent and the exploration of mothers interesting, but I can not help but feel slightly underwhelmed by the events. It may because I knew the story going in, and felt more like I was playing out something that was already familiar and not needing further discussion.The above points aside, this is an enjoyable romp through a fantasy land, and when you consider it was novelized in 1911, it is even more impressive. However, I must grade the book on how it stands up today, and not how it would have stood in its time of publication. With that in mind, I enjoyed the book for what it is, but it is a story that does not need to be told more than once. I suppose I may just be a bitter adult in saying that, but so be it.

The Verdict:

There are better fantasy adventures out there, but if you simply must read the classics or are interested in coming of age stories and the transition from childhood to adulthood, this is a solid bet. Again, I can only grade my own experience with the book, which was a little above mildly enjoyable. I am sure there are others who adore it, and you are free to take their word for it as well.

3.5/5

Next Up:

Fallen by David Maine.

Saturday, January 2, 2010

The Art of Being There

Title: Girl in a Red River Coat

Title: Girl in a Red River CoatAuthor: Mary Peate

Published: 1970

Pages: 130

Reading Time: December 18-December 22, 2009.

Plot Teaser:

An autobiographical fictionalization of growing up in 1930s Montreal, Quebec, Girl in a Red River Coat captures the mood of a particular time and place, through the eyes of childhood. Wrapped in innocence and clarity, Mary Peate's novel echoes the dominant feelings of the Depression era.

How I Got It:

This book was stuck between a collection of others in my parents' basement. My youngest sister left a lot of her old books behind when she moved out, and this was one of them. It caught my attention because of its stark cover and subject matter. I picked it up at some point in the summer of 2009, simply going through a mix of other fiction in the basement, most of which were romance novels.

The Review:

For any work of art to have mass appeal, it needs to present itself in a way that is relatable to its audience. In the realm of fiction, many stories rely on a main character who the audience can sympathize with and one who acts as the eyes and ears of the reader. Mary Peate's Girl in a Red River Coat places Peate herself at the centre of the story, and it is through her mind that we come to understand her life and the lives of those around her. Thankfully, Peate's views are never dull and her reflections in the novel show great insight, while transporting the reader to a very tangible time and place.

This book takes place in 1930s Montreal, Quebec, in the midst of the Great Dep

ression. Small touches like references to the price of bread and other items really help bring the somber reality of the era to the forefront. While it focuses on Peate and her everyday activities, such as sitting on the porch talking with friends from school and her neighbours, it is the bigger picture that forms around these experiences that gives the book meaning and power. The name of the book itself is not explicitly explained, and Peate's red river coat is only mentioned in a few paragraphs, but the symbolism of Peate as 1930s everygirl is quietly obvious. The book may focus on Peate, but it is about the collective experience of people, particularly children, growing up during this difficult era.

ression. Small touches like references to the price of bread and other items really help bring the somber reality of the era to the forefront. While it focuses on Peate and her everyday activities, such as sitting on the porch talking with friends from school and her neighbours, it is the bigger picture that forms around these experiences that gives the book meaning and power. The name of the book itself is not explicitly explained, and Peate's red river coat is only mentioned in a few paragraphs, but the symbolism of Peate as 1930s everygirl is quietly obvious. The book may focus on Peate, but it is about the collective experience of people, particularly children, growing up during this difficult era.The book's enjoyment is largely a result of its complete lack of pretense. The chronicled experiences, such as riding the street car, going to the store, being insulated in a Catholic community, and learning about the opposite sex, are told with very matter-of-fact prose. They simply state things as they were, which gives the book a very innocent and honest quality. While there are certainly little quips and jabs at certain aspects of community and family life, most passages are incredibly straight forward and deadpan. For example:

"On Holy Thursday, which was a school holiday, we were encouraged to visit seven churches in order to gain a plenary indulgence, which meant that all the sins would be wiped from your soul and you could start from scratch. You were supposed to walk from church to church, not ride, and you weren't supposed to speak as you walked, or, we were told, the plenary indulgence wouldn't go into effect."

This type of simplicity permeates Peate's prose, and its subtlety shows a very neutral retelling of this part of the author's life. What is wonderful about this style of writing is that it does not go out of its way to beat you over the head with a particular message or to make you feel horrible for the people during the Great Depression. Instead, it gives a very level-headed account, with enough heartfelt perspective and a certain level of naivite that force admiration from the reader.

I should mention that the main story tracks Peate's quietly vindictive relationship with a sick aunt who has moved in to live with her family and sleep in her bed, which grounds the narrative in something the audience can relate with. Peate goes back to this struggle periodically in the book, and resolves it with as much grace as she does the rest of the story. Despite only being 130 pages, this record of 1930s life in Montreal is packed with social commentary, real life drama, and it offers an engaging snapshot of a girl's seemingly simple life.

The Verdict:

I would recommend this book to anyone who enjoys autobiographical fiction, history, or books in general. It may be a thin and quick read, but its mental pictures, reflections, and emotions have staying power. I can imagine it being particularly enjoyable for people who went through this era, but it is highly recommended for young readers as well. There are enough social issues, namely related to religion and the Quebec language issue, for it to be relevant to a wide audience.

4/5

Next Up:

Peter Pan by J.M. Barrie.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)